![[Iceland 1988 Stamp Day]](chis.jpg) |

![[San Marino 1974 ancient weapons and armor series]](chsm.jpg) |

![[Sweden's 1972 Lady with the Fan]](chs.jpg) |

![[Denmark's 1976 The Postillion]](chdk.jpg) |

| Foreword by Toke Nørby This page was prepared by Chuck Matlack who passed away on 3 June 1996. In December 1997 I found that Chuck's pages were removed from the site where they have been since 15 December 1995. I have never met Chuck in person or even seen a picture of him but he was one of my very first and very good e-mail friends. After Chuck's death, his friend who maintained Chuck's pages at his "old" site told me that I was welcome to host his pages after they have been removed, if I would like to do that. So, what you see here are Chuck's five pages taken together in one single page. For more information on Slania you can contact the Czeslaw Slania Study Group (address at the end of this page). Please enjoy Chuck's tribute to Czeslaw Slania. |

![[Iceland 1988 Stamp Day]](chis.jpg) |

![[San Marino 1974 ancient weapons and armor series]](chsm.jpg) |

![[Sweden's 1972 Lady with the Fan]](chs.jpg) |

![[Denmark's 1976 The Postillion]](chdk.jpg) |

| About the Illustrations The 40 kronor souvenir sheet (the border with additional text has not been included in the illustration) is a fine example of traditional single color engraving. Here, Slania illustrates the last of a series of three pieces taken from the works of Auguste Mayer. This one was issued by the Icelandic Post for Stamp Day 1988, and shows an early settlement in Nupsstadur in 1836. The pink and gray 20 lira issue from San Marino is a single from the series of eight that Slania did for that government in 1974 depicting ancient weapons and armor. "The Lady with the Fan" was painted by Alexander Rosin in 1768. It depicts the artist's wife in the style of the time, and is a particularly good example of the subtle colors and texture which a master engraver can bring to life. This 75 ore stamp was issued by Sweden in 1972. Otto Bache painted "The Postillion" in 1878. Both a souvenir sheet (illustrated) and a stamp single was issued for HAFNIA 76 held in Denmark. The rich colors and fine details, particularly in the horses, illustrate what depth a master engraver can evoke. Denmark released this 130 øre sheetlet in 1976. (Again, the border with additional text has not been included in the illustration). |

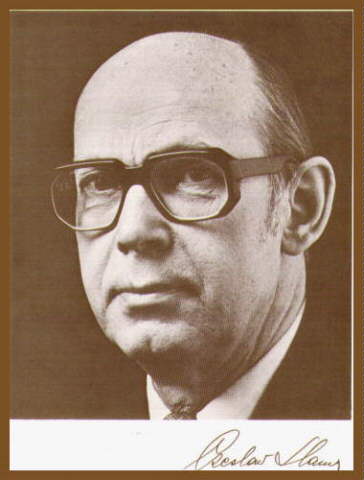

| Czeslaw Slania (pronounced Chess-wav Swan-ya) was born in Silesia, Poland in 1921. He entered the Cracow School of Fine Arts in 1945. Employed by the Polish Government Printing Works, Slania engraved his first stamp for Poland in 1951. He came to Sweden in 1959, and engraved a stamp for Sweden in 1959. Slania formally joined the Swedish Postal Service as a full time engraver in 1960. Since then, he has been appointed Royal Court Engraver in Sweden, Denmark and Monaco, and won numerous awards for both the beauty, speed and proliferation of his engravings. Because of the number of items he has engraved and their beauty, Czeslaw Slania is the world's most famous engraver.

Picturered here in a 1980 photo, he is now 74 and still amazing people around the world with his skill, accuracy and speed. Although he already has the world's record for the greatest number of fine engravings, he has a personal goal of 1,000. Some engravings, like his portraiture of Queen Margrethe II of Denmark, has been used on dozens of different stamps and postal stationary items, but Slania counts this engraving as only a single piece of work. Those of us within the Czeslaw Slania Study Group are eagerly watching as he approaches his goal. We join the Poles in wishing Slania Sto Lat!, or 100 years! |

What is engraving? Engraving is an art process where lines, dots and dashes are cut into a soft metal plate with a tool called a burin. The engraving is done life size and in mirror reverse. Up to 10 lines per millimeter are cut at depths varying from 0.01 to 0.08 mm to give the effects of shadows, highlights and contours. Because engraving requires long years of study and an extended apprenticeship, it is used for high security documents such as postage stamps and banknotes. Fine art productions usually require that only a few images are produced from each plate. In stamp production, many thousands, if not millions, of impressions are made. Although the production of the actual engraving plate is similar, the production of the plates used to print stamps is the work of an entire sub-industry. After the final artwork has been approved, the engraver cuts the major engraving lines as an outline into cellophane which is eight times larger than the final design size. The cut cellophane is placed over an asphalt-coated zinc plate in mirror image position. Lines are cut into the asphalt, tracing the cellophane outline, with a steel pin. The plate is placed into a nitric acid bath which etches the design into the zinc, and the asphalt is then removed. A machine called a pantograph then traces the etched outline onto a piece of soft 18.5 x 20.5 mm steel. This reduces the design by a factor of eight so that the outline is the actual size of the stamp. This crude mirror image on soft steel begins the real art of engraving. Using a burin and magnifying glass, the engraver carves up to ten lines per millimeter into the soft steel. By carving patterns of lines, dots, and cross-hatch patterns, he forms the mirror image into the stamp-sized field of steel. Many lines, deeply carved and close together, produce heavily shaded areas on the final image. Lighter areas, such as a cheek highlight, contain relatively few shallow lines. Whatever the desired effect, the engrave must get it right the first time. There is no such thing as an eraser on a burin. This exacting process usually requires between four and six weeks per engraving. Constant proofs are pulled during this process to insure that the work is proceeding according to plan. The finished plate is then sent to the printing works, where it is tempered in an 800 C sodium cyanide bath for 45 minutes, and then quenched in water. This hardens the plate so that it can withstand further processing. The hardened plate then has its image transferred to a soft steel transfer roller called a molette. Four equally spaced positive images are pressed into the molette, which is then tempered the same way that the original steel plate was tempered. The positive image of the molette is then impressed onto the printing cylinder, giving a negative (mirror) image. The printing cylinder is steel covered with a thin layer of copper to insure a good impression. For a typical definitive-size stamp, the molette would impresses 10 rows of 34 images each for a total of 340 images. The printing cylinder is then chrome plated to harden its surface, and is then ready to be mounted on a press and the actual printing started. There are many varieties of this basic process, particularly where multicolor printing is required, but the basic engraving process is the same. Engraving is a laborious process to learn, requiring long apprenticeship, consummate physical dexterity, a highly developed artistic sense and patience. Because of this, most of the world's stamp production is now done by photographic processes which require none of the master engraver's traits. Why collect Slania's work?

|

|

Other Czeslaw Slania pages on the web:

|

|

Czeslaw Slania Societies:

|

|

![]()

Back to Toke Nørby's

home page

Uploaded on 22 December 1997 - last modified 2012.12.26