![]()

As mentioned on the previous page on Kranhold, he sold his large collection in 1925 to the stamp dealer Charles Philips. After the sale and after the many articles in various philatelic journals, both about Denmark's first postage stamp, but also about the Danish West Indies stamps, it is clear that he never later took these issues up again. It did not keep famous philatelists as G. A. Hagemann, Ernst M. Cohn, the Dane John Spohr and Roland King-Farlow away from returning to the pioneering work Kranhold had done. In 1925 G. A. Hagemann wrote to Kranhold and regretted that he had not heard from him after a letter of 9th August 1924. Hagemann asked for the copies of articles Kranhold had promised him. In his letter, Hagemann told Kranhold, that in his large stock of old DWI stamps he had a half-sheet of 2 cents red and a half sheet of the 8 cents brown - imperforate essays and wrote that he considered them to be the only ones and that he had sold some to U.S. dealers. He had a block of four of each back and asked if Kranhold was interested in purchasing. We do not know what Kranhold responded, but it is quite certain that he was not interested any more. Divorce and later Depression in the U.S. As late as 1949 Roland King-Farlow wrote (See letter to the right.) and wondered why Kranhold had been silent after his many articles - but Kranhold probably told him about the sale of his stamps. Another famous collector, Ernst M. Cohn, wrote in 1949 to Kranhold: 1629 Princess Avenue 11 August 1949 Mr. A. A. Kranhold Dear Mr. Kranhold: Unfortunately, I do not yet have my philatelic library in our new apartment, but if I remember correctly, the multiple use of frame plates has been studied in extense since you discovered it. Caroe, Hagemann, and others have also published their findings, most of which are summarized in Hagemann's big opus. This multiple use is also evident from some of the plates which contained one or more thick frames, the plate positions being identical for several groups of öre and cents values. The importance of these discoveries for dating and plating purposes is obvious. My own collection is rather small, too, since I sloughed off all but Scandinavia, then all stamps of these countries after about 1880, then postal stationery, locals, and Xmas seals, and finally all of the cheap older stamps which are not distinguished by some oddity or other. I have gravitated more toward cancels on entires, stampless covers, a few minor varieties but most of all philatelic literature. Last year I acquired Philips Denmark Catalogue, a leather-bound copy originally owned by a Mr. Foster S. Shilds, for the healthy sum of $ 12.50. Inspite the price it commands I think its value is not generally recognized by many specialists; it is, as far as I know, the only catalogue which list prices for numeral cancels of EACH value of the classic stamps. All other lists I have seen concern themselves only with the cheapest stamps. Yours must have been a magnificent collection, indeed, and I am only sorry that I was but 5 years old when it was sold. Sincerely yours,

Nancy Kay Erickson It has been difficult for a complete stranger (me) to select what to show to describe the (hopefully now famous :-) philatelist still keeping some personal and family information, Nancy provided, in secret. Not because the information is that secret but it's just not needed to describe the person for other philatelists. I am pleased now to know many family members and am pleased that they gave me so much personal information about Arno A. Kranhold. |

![]()

| Bibliomania by A.A. Kranhold (typed by his granddaughter Nancy Kay) I cannot explain just why I fell a victim to Bibliomania. It was unpremeditated. Bibliomania may be defined as that black plague which ravages purses and drives the soul into a high fever of acquisition, akin to the Duce's territorial visions. Mere reading is not the moisture, nor the warmth, which accounts for the growth of a collector to his full bloom. Nor is it the acquisition of a few old tomes with the Borer's progress very evident; not even the new and splendid limited editions in their pristine just-off-the-press garb. Hang it all, I cannot tell you what particular weaknesses are most susceptible to the contagion. I only know when I first felt the symptoms.

In front of the store were two table-high stands on which reposed the down-at-the-heel with the unknowns, "Your Choice, 54 - 104". What inveterate reader, even if engaged on a mission of seemingly grave import, but will slow up a bit at the sight of books? And so did I. My steps lagged - at the corner of the further stand, I literally, or shall I say "literarily", peeked over my shoulder. And then right about face to glance at such titles as it were possible to see on the rickety stands. And I glanced further at the indiscriminate choice in the windows. There reposed a Godey Magazine of 1861, rubbing elbows with a Currier and Ives print of Niagara Falls. Lo! Next to the print, was an old map, in the corner pencilled date, "1589" and "Ortelius." Ortelius, the famous Dutch cartographer, whose map-engraving ability remains unsurpassed unto this day! I peered through and between the deep piles. The interior seemed to consist of books and books, literally oceans of them. They seemed not unlike the swarming salmon, rushing the rapids of the Columbia River in the spring. I summoned courage and entered - but not boldly. No corps of clerks rushed to the door. In fact, no one paid any attention to me. The proprietor did not raise his eyes from the dozen or so gold coins on the battered desk in front of him. Fascinated, I watched him pick up each one with reverence, inspect it briefly, and then slowly lay it down in the velvet-lined compartment of a small leather case. The shelves extended to the ceiling. My very important business was relegated to an excellent haven for the time being, and I walked up and down the narrow passages. As casually as the intake of breath, came the first bacteria of that dread scrouge, Bibliomania. I had picked up a slender volume, inexpensive board bindings, the title "Love and Laughter". What a series of delicious illustrations! I can almost see Alexander King's impish smile as his pencil traced these devilish drawings. It was an anthology of verse, and since the English course at my "Railroad" University had featured only way-bills, bills of lading, and the like, it was not strange that I failed to recognize such names as Donne, Carew, Suckling, Cartwright, Herbert, Prior, Herrick, Cowley, Waller, and others of the Elizabethan period. I had read a bit of Milton, and a great deal of Shakespeare, but here was disclosed a new, (to me) fresh field of English literature. I read in utter oblivion of my surroundings, of my errand. Herrick's lyrics, how nice this rhymes! Donne's harsh but beautiful verse - the others, all more or less amorous in spirit. Then I realized with a start that I was a "book-poacher", but still no one had paid any attention to me. What a delightful retail establishment! We were not vendor and vendee, but book-fellows. I had been here an hour when my commercial instincts asserted themselves, and emphasized the importance of trade in this sorry scheme of things. One cannot buy books without an income. Alas, it was too true! The proprietor took my fifty cents as one who confers a favor. I agreed then; now my obligation has attained immeasurably compounded proportions. My haunting recollections of certain worthless embossed certificates can always be dissipated in the thoughts of the humble library which grew out of this casual purchase.

Where could I obtain some inexpensive editions of these poets, my new found friends? I recalled that when an acquaintance returned from Europe, he spoke of the extensive second-hand book stores of London. Did they issue catalogues and how might I obtain their addresses? There were the advertising columns of The London Mercury, the Book Selection of the London Times, The Manchester Guardian, and a few American periodicals. A number of requests by post, and there followed a steady stream of lists or catalogues, the first ones accompanied by courteous letters from bookly gentlemen. The flow continues to this date. My prayers were answered. The wares of every post, represented in my anthology, were on sale in divers editions, - the descriptions were generously accurate, precise, and I soon learnt I need have no fear that wares were misrepresented as to condition, etc. The catalogues were often literary in their own rights, the editors speaking learnedly and apparently authoritatively, relative to the work or the author. I use the term "second-hand" with reservations; in fact, I do not like it. In a sense, all books acquire this category except perhaps those modern and current issues just off the presses and decidedly "Eight avenue" in their virginal dust jackets.

I glance at the humble shelves where repose the works of Donne. There is that beautiful edition of his first collected poems, the 1633 edition, a sturdy black morocco binding, clean as a hound's tooth. This bears a penciled notation on the inside of the front cover, "Collated and found perfect". I reverently pull out this volume, turn to page 151 where is that magnificent "Elegie", "The Autumnall", and read: "No spring, nor summer Beauty had such grace, Has anyone ever written more beautifully concerning the matriarch of the family, excepting perhaps the remotely commercial-minded Edgar Guest?

The significance of the inscription rests with the Dean. I believed it referred to the long wait the poet endured before his preferment at the hands of King James. Professor Sparrow, who very courteously condoned my presumption, did not agree. He expressed his great interest in the discovery of this volume and apologized for conveying the information to the famous bibliographer of Donne, Geoffrey Keynes. Perhaps the post carried the volume, or it furnished inspiration for some of the sermons delivered in St. Paul's Chapel, and where James scrupulously attended. This is assured splitting hairs, and of little interest to you, be you auditor or reader, but to a Donne enthusiast, the discovery of another Kohineer would be of less interest. I have a document in Latin, the date as of 1614, and conferring on John Donne a certain appointment. I have not had it translated; my own Latin has become as Sanskrit, but hold it for a future date when the occasion warrants and I can invoke the assistance of an excellent Latin scholar. I parted with but two pounds for this treasure. When I look at these first editions, I am reminded of a bit of anonymous verse, of the date of 1740. I wonder who wrote: Upon The First Edition of Books. Turning to the bottom shelf of the tall case, especially built by a janitor-cabinet-maker out of ordinary packing boxes, to accomodate those large paper editions, I find another heart's treasure. There is Edmond Waller's own copy of Homer, a massive tome in the original letter binding. The date is 1606, and the text is Latin. Edmond, in a very execrable hand, scribbled verses, and "bad" ones, on the first two pages and the last one, and also affixed his signature, "Edm. Waller". The book was in the possession of the Waller descendants until the year 1901, nearly three hundred years, and then to the block in exchange for pounds and pence, - what a travesty! Shall I take to the silver-smith, what with the advanced price of the metal, the old key-wind silver watch which grandfather carried into the California Eldorado in 1849? I trust that the Waller fortunes had been reduced to a point where this sacrifice was necessary to keep body and soul in harmonious relationship. If you have not read Waller's "Go, Lovely Rose", please do. "Her feet, from 'neath her petticoat,

Is it not a pretty conceit - so delicately turned on this rhymster's lathe?

The latter was addressed to William Godwin of not inconsiderable note as a writer; he was Shelly's father-in-law. She extends a cordial invitation to William to see her at Drury Lane - after the show. Except they be sets in uniform bindings, I do not care to find an author's works segregated in a group. Why, I cannot say. It is not consistent, but there is a certain zest in the discovery of a volume, not recorded in memory's index. Therefore, my ten or twelve volumes of Charles Fingers - all affectionately inscribed to myself, are scattered on divers shelves. Finger has sailed the Seven Seas. He writes from the shoulder, but his is another voice in the wilderness. Then I value, if only for folly's sake, that "booklegged" copy of Ulysses, the one by James Joyce. Poor Joyce, now almost blind. This copy is out of the Shakespeare press, Paris. My friend, (?) the book-seller, took me aside: - "It is just arrived, look at it, everywhere - one-hundred dollars and over it brings; it is yours for only seventy-five". I was like putty in his hands. When I reflect on the cost of his addenda to any lexicography, I read Erasmus' "In Praise of Folly". I have never been able to wade more than half across this stream of Joyce's subconsciousness, but I do not enlist with those who dismiss it as a piece of pornographic tripe. "So happens it, the winde covers each passion May I qualify my expressed satisfaction in the possession of Mosher's Bibliot as sufficing for all literary appetites, if marooned by chance, or otherwise, on a desert isle? How can I leave out William Shakespeare? For my set of twelve volumes, fabrikoid bindings, with the imprint of the famous originator of the Blue Books, E. Haldeman Julius, I paid $3.69. Nice clear print, veritable First Folios, literarily speaking. What matters it that William thieved many of his plots from the 13th and 14th century Italians? Or that a few Bacon enthusiasts are endeavoring to steal his thunder for Sir Francis? To my verse writing friends, I commend his: "The poet's eye in a fine frenzy rolling, It is to despair. These are fancies of my own, by And these are also my sentiments." |

![]()

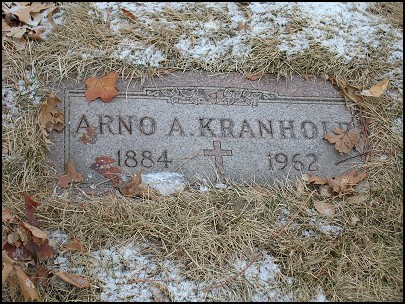

Fig. 8. Hillside Cemetery - Minneapolis.

| 27.01.2012 |

|